Jean-Paul Sartre Rejects the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964: “It Was Monstrous!”

In a 2013 blog post, the great Ursula K. Le Guin quotes a London Times Literary Supplement column by a “J.C.,” who satirically proposes the “Jean-Paul Sartre Prize for Prize Refusal.”

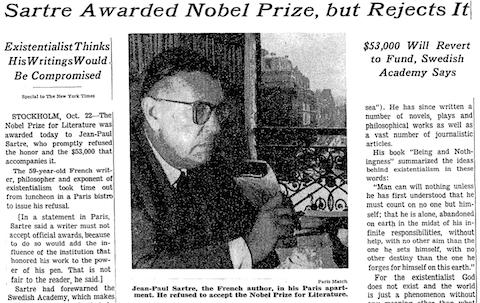

“Writers all over Europe and American are turning down awards in the hope of being nominated for a Sartre,” writes J.C., “The Sartre Prize itself has never been refused.” Sartre earned the honor of his own prize for prize refusal by turning down the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964, an act Le Guin calls “characteristic of the gnarly and counter-suggestible Existentialist.” As you can see in the short clip above, Sartre fully believed the committee used the award to whitewash his Communist political views and activism.

But the refusal was not a theatrical or “impulsive gesture,” Sartre wrote in a statement to the Swedish press, which was later published in Le Monde. It was consistent with his longstanding principles. “I have always declined official honors,” he said, and referred to his rejection of the Legion of Honor in 1945 for similar reasons. Elaborating, he cited first the “personal” reason for his refusal

This attitude is based on my conception of the writer’s enterprise. A writer who adopts political, social, or literary positions must act only with the means that are his own—that is, the written word. All the honors he may receive expose his readers to a pressure I do not consider desirable. If I sign myself Jean-Paul Sartre it is not the same thing as if I sign myself Jean-Paul Sartre, Nobel Prize winner.

The writer must therefore refuse to let himself be transformed into an institution, even if this occurs under the most honorable circumstances, as in the present case.

There was another reason as well, an “objective” one, Sartre wrote. In serving the cause of socialism, he hoped to bring about “the peaceful coexistence of the two cultures, that of the East and the West.” (He refers not only to Asia as “the East,” but also to “the Eastern bloc.”) Therefore, he felt he must remain independent of institutions on either side: “I should thus be quite as unable to accept, for example, the Lenin Prize, if someone wanted to give it to me.”

As a flattering New York Times article noted at time, this was not the first time a writer had refused the Nobel. In 1926, George Bernard Shaw turned down the prize money, offended by the extravagant cash award, which he felt was unnecessary since he already had “sufficient money for my needs.” Shaw later relented, donating the money for English translations of Swedish literature. Boris Pasternak also refused the award, in 1958, but this was under extreme duress. “If he’d tried to go accept it,” Le Guin writes, “the Soviet Government would have promptly, enthusiastically arrested him and sent him to eternal silence in a gulag in Siberia.”

These qualifications make Sartre the only author to ever outright and voluntarily reject both the Nobel Prize in Literature and its sizable cash award. While his statement to the Swedish press is filled with polite explanations and gracious demurrals, his filmed statement above, excerpted from the 1976 documentary Sartre by Himself, minces no words.

Because I was politically involved the bourgeois establishment wanted to cover up my “past errors.” Now there’s an admission! And so they gave me the Nobel Prize. They “pardoned” me and said I deserved it. It was monstrous!

Sartre was in fact pardoned by De Gaulle four years after his Nobel rejection for his participation in the 1968 uprisings. “You don’t arrest Voltaire,” the French President supposedly said. The writer and philosopher, Le Guin points out, “was, of course, already an ‘institution’” at the time of the Nobel award. Nonetheless, she says, the gesture had real meaning. Literary awards, writes Le Guin—who herself refused a Nebula Award in 1976 (she’s won several more since)—can “honor a writer,” in which case they have “genuine value.” Yet prizes are also awarded “as a marketing ploy by corporate capitalism, and sometimes as a political gimmick by the awarders [….] And the more prestigious and valued the prize the more compromised it is.” Sartre, of course, felt the same—the greater the honor, the more likely his work would be coopted and sanitized.

Perhaps proving his point, a short, nasty 1965 Harvard Crimson letter had many, less flattering things than Le Guin to say about Sartre’s motivations, calling him “an ugly toad” and a “poor loser” envious of his former friend Camus, who won in 1957. The letter writer calls Sartre’s rejection of the prize “an act of pretension” and a “rather ineffectual and stupid gesture.” And yet it did have an effect. It seems clear at least to me that the Harvard Crimson writer could not stand the fact that, offered the “most coveted award” the West can bestow, and a heaping sum of money besides, “Sartre’s big line was, ‘Je refuse.’”

Source and image.

Follow

Follow