Tasting colours and seeing sound: Synaesthesia

“One hears a sound but recollects a hue, invisible the hands that touch your heartstrings,” wrote Vladimir Nabokov, 20th century novelist. He experienced a curious condition called synaesthesia, which comes from the Greek words syn (together) and aisthesis (perception) and literally means ‘joined perception’. The condition basically causes a fusion of sensory perceptions in which the stimulation of one sense produces a perception in another sense.

Synaesthetes are otherwise neurologically normal people who experience parts of the world in extraordinary way, sometimes without realising it. To them, the city skyline could taste of tomato soup, the musical note C could look like red, and Monday could be perceived as sharp and spiky.

Initially thought to be a rare condition, it’s now estimated that up to 4% of people experience a form of synaesthesia. It’s also thought to be a genetic, passed down from parent to child—Nabokov’s mother also experienced it, but they often argued about their perceptions because every synaesthete experiences joint perceptions in individual ways, each as unique as fingerprints. Sometimes the differences are broad, encompassing the different combinations of senses: one person might be able to hear smells, while another feel sounds, and yet another can taste shapes. Some people even experience synaesthesia with three or more senses, though that’s rare. Or, the differences might be within associations: Nabokov perceived each letter of the alphabet as having its own precise hue. The perceptions of individual synaesthetes are highly consistent. For him, b was always the colour of burnt sienna, t was always pistachio green and v was always quartz pink, but for his mother, the colours were completely different.

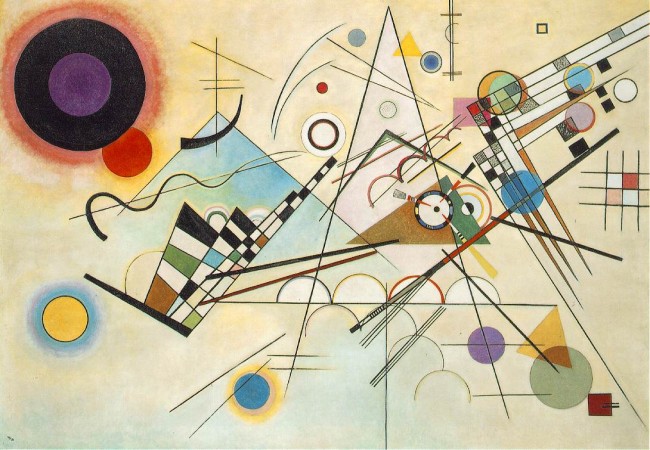

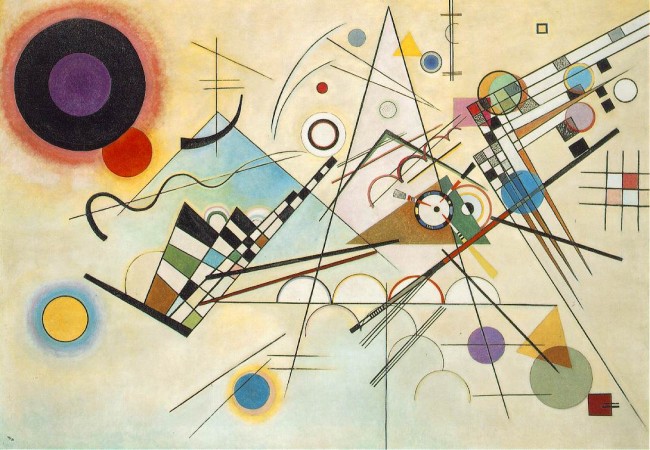

Nabokov and his mother experienced one of the most common form of synaesthesia: grapheme-colour, i.e. associating different colours with different letters, numbers and words. Nobel Prize winning Physicist Richard Feynman also experienced this type of synaesthesia, reporting that he saw equations in colour (n was “mildly violet-bluish”). History is actually teeming with synaesthetes, from composer Franz Liszt to abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky to actress Marilyn Monroe, but research on the condition has only begun quite recently.

Brain imaging has shown that for grapheme-colour synaesthetes, words activate both the language centres of their brain and the neighbouring visual cortex, which deals with vision and colour processing. Similarly, when colour-hearing synaesthetes hear certain words, they have displayed activity in areas of the visual cortex associated with processing colour.

Somehow, these two different sections are cross-activated, but it’s currently uncertain what causes this. It’s been suggested that it could be caused by ‘cross-wiring,’ i.e. neurons and synapses in one sensory system could be crossing to another. Studying infants’ responses to sensory stimuli has led researchers to believe that everyone possesses crossed connections early in life, and they are only later refined and segregated—so adult synaesthetes could simply keep some of these connections, possibly due to genetic abnormalities.

Unravelling the mystery of synaesthesia is fascinating because it provides a unique opportunity to investigate human consciousness, and hopefully come to understand the processes by which our brains create perceptual reality. A current mystery of consciousness is how we simultaneously bind our perceptions together into a whole—for example, when we drink tea, we can see its colour, smell its scent, taste its taste and feel its texture all at once, and somehow our brain manages to bind all these perceptions into one concept. Studying synaesthesia could help us understand this, and subsequently understand how we perceive our world at large.

Unravelling the mystery of synaesthesia is fascinating because it provides a unique opportunity to investigate human consciousness, and hopefully come to understand the processes by which our brains create perceptual reality. A current mystery of consciousness is how we simultaneously bind our perceptions together into a whole—for example, when we drink tea, we can see its colour, smell its scent, taste its taste and feel its texture all at once, and somehow our brain manages to bind all these perceptions into one concept. Studying synaesthesia could help us understand this, and subsequently understand how we perceive our world at large.

Interestingly, it could even help us understand more elusive ideas, such as the neural basis for metaphors. Connections between sensory areas of the brain might play a crucial role in their formulation—consider how we might describe a cloud as “soft” or a cheese as “sharp”. When you think about it, synaesthesia is a metaphor for metaphors themselves.

Fuge L (2012-11-07 00:30:18). Tasting colours and seeing sound: Synaesthesia. Australian Science. Retrieved: Jul 19, 2025, from http://ozscience.com/history/tasting-colours-and-seeing-sound-synaesthesia/

Follow

Follow

Oh that we could have had living science such as this at school! I’m sure more pupils would have switched on, instead of yawning through the abstractions on the blackboard.

I do recall synaesthesia as a seven year old: certain shapes would instantly trigger a word in my head. A useful starting point for discussion of perception/association etc – but there was just nobody to ask, no slot in the curriculum – and alas no Google. Now the capacity has evaporated and, who knows, it might have been a foundation for poetry.

As for ‘thinking skills’ for young people… they took another 50 years to appear here in UK, while French schools were well ahead. Here’s to Lauren and all people who have an enquiring passion for science, and for communicating it.

As a kid I thought everyone experienced the world as I did: sounds and the feeling of touch on my skin had color, words had taste… I grew older but some of these remained, the strongest being touch-color.

I was in shock many years ago when I read an article on Scientific American about synaesthesia and immediately identified my “condition”: I was one of them!

It is nice to know my brain is wired like this and it drove me even more to my field of work and passion, neuroscience. I hope I can step inside of this subject and help uncover what’s behind this beautiful and amazing machine called brain.