Does my Science look big in this? October edition

Science this month tackled many of the big questions: Where did life on Earth originate? How do we learn? How can we live healthy lives? and, What is it with scientists and sticky-tape?

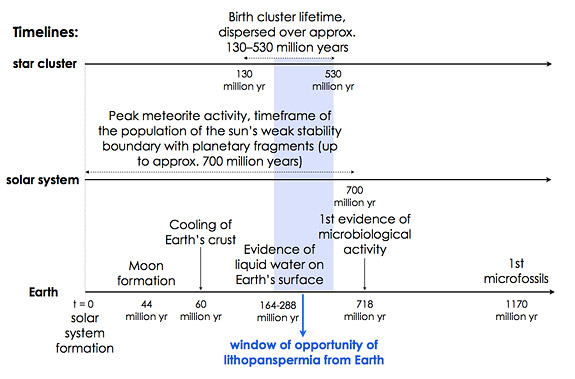

Lithopanspermia is the idea that basic life forms are distributed throughout the universe via meteorite-like planetary fragments. Eventually, another planetary system’s gravity traps these roaming rocks, which can result in a transfer of any living cargo.

Researchers reported that under certain conditions there is a high probability that life came to Earth — or spread from Earth to other planets — during the solar system’s infancy when Earth and its planetary neighbors orbiting other stars would have been close enough to each other to exchange lots of solid material.

Previous research suggests that the speed with which solid matter hurtles through the cosmos makes the chances of being snagged by another object highly unlikely. This research reconsidered lithopanspermia under a low-velocity process called weak transfer in which solid materials meander out of the orbit of one large object and happen into the orbit of another. In this case, the researchers factored in velocities 50 times slower than previous estimates, or about 100 meters per second.

Using the star cluster in which our sun was born as a model, the team conducted simulations showing that at these lower speeds the transfer of solid material from one star’s planetary system to another could have been far more likely than previously thought.

The researchers suggest that of all the boulders cast off from our solar system and its closest neighbor, five to 12 out of 10,000 could have been captured by the other. Earlier simulations had suggested chances as slim as one in a million.

This research highlights that life could have originated away from earth. The theory that it did is yet to be demonstrated.

Research has again shown that you can indeed “teach old dogs new tricks.” The brain you have at any stage of your life is not necessarily the brain you are always going to have. It can still change, even for the better. This time however the researchers observed changes in the brain’s white matter.

Most people equate “gray matter” with the brain and its higher functions, such as sensation and perception, but this is only one part of the anatomical puzzle inside our heads. Another cerebral component is the white matter, which makes up about half the brain by volume and serves as the communications network.

The gray matter, with its densely packed nerve cell bodies, does the thinking, the computing, the decision-making. Projecting from these cell bodies are the axons – the network cables. They constitute the white matter. Its color derives from myelin – a fat that wraps around the axons, acting like insulation.

This study looked at a really complex, long-term learning process over time, actually looking at changes in individuals as they learn a language. The work demonstrates that significant changes in the mylenation were observed in adults as they were learning. This research demonstrates how learning is a many step process in our brain.

The flip-side of learning is the persistence of misinformation. Why does that kind of ‘learning’ stick? A new report explores this phenomenon. According to the researchers rejecting information actually requires cognitive effort. Weighing the plausibility and the source of a message is cognitively more difficult than simply accepting that the message is true. If the topic isn’t very important to you or you have other things on your mind, misinformation is more likely to take hold.

Misinformation is especially sticky when it conforms to our preexisting political, religious, or social point of view. Because of this, ideology and personal worldviews can be especially difficult obstacles to overcome.

Even worse, efforts to retract misinformation often backfire, paradoxically amplifying the effect of the erroneous belief.

Though misinformation may be difficult to correct, all is not lost. According to the report, these strategies can set the record straight.

- Provide people with a narrative that replaces the gap left by false information

- Focus on the facts you want to highlight, rather than the myths

- Make sure that the information you want people to take away is simple and brief

- Consider your audience and the beliefs they are likely to hold

- Strengthen your message through repetition

Research has shown that attempts at “debiasing” can be effective in the real world when based on these evidence-based strategies.

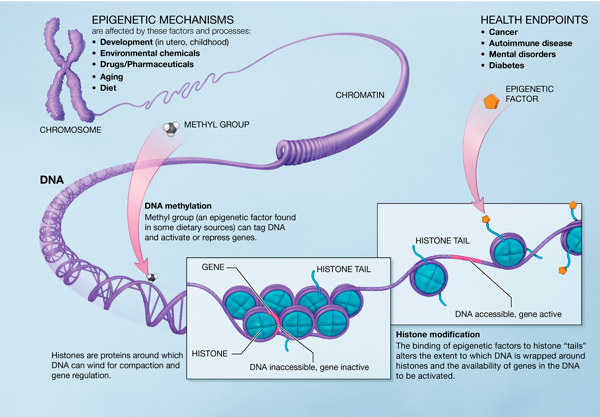

What a mother eats when pregnant makes a huge difference in the health of her child. Now, new research in mice suggests that what she ate before pregnancy might be important too.

According to a new research report published online what a group of female mice ate – before pregnancy – chemically altered their DNA and these changes were passed to her offspring. These DNA alterations, called “epigenetic” changes, drastically affected the pups’ metabolism of many essential fatty acids.

These results could have a profound impact on future research for diabetes, obesity, cancer, and immune disorders.

Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, had won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics. The pair were honored for helping develop a simple technique that allowed the isolation of graphene, a sheet of carbon a single atom thick, using sticky-tape.

Now an international team led by University of Toronto physicists has developed a simple new technique using Scotch poster tape that has enabled them to induce high-temperature superconductivity in a semiconductor for the first time. The method paves the way for novel new devices that could be used in quantum computing and to improve energy efficiency.

Does my science look big in this? is an idiosyncratic, personal, monthly look at what I found most interesting from science published in September.

Orrman-Rossiter K (2012-10-01 06:54:20). Does my Science look big in this? October edition. Australian Science. Retrieved: Mar 14, 2026, from http://ozscience.com/science-2/does-my-science-look-big-in-this-october-edition/

Follow

Follow

1 thought on “Does my Science look big in this? October edition”

Comments are closed.