Australia’s evolving drug landscape

This year we saw Australia put into force a new patent law. An intellectual property system that was Australia’s most comprehensive in over two decades. It came into effect on 15 April 2013 and no one knew exactly what to expect from it.

We have seen with cases like India, how one country’s patent laws can send ripples and disrupt the entire system. And, in the case of Thailand, how a country can take matters into its own hands to enact a public good.

It really all centres around compulsory licensing. A compulsory license, in simple legalese, is the use of a patented innovation that has been licensed by a state without the permission of the patent title holder. This started over a decade ago, when the World Trade Organization adopted the “Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health” at its 4th Ministerial Conference in Doha. At the time, many anticipated that this would lead nations to more frequently claim compulsory licenses for pharmaceutical products.

The TRIPS Agreement allows governments to license the use of patented inventions to someone else without the consent of the patent owner. It does not and should not prevent nations from taking measures to protect public health — that was the way it was billed and sold. In dealing with public health epidemics, such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, countries such as Brazil, India, Thailand, Indonesia and Ecuador have used compulsory licensing to reduce the prices of pharmaceutical drugs for their citizens. What has been seen is a significant spike in use of compulsory licensing in years since Doha.

So where does Australia sit in this spectrum?

Last month, the Australian Parliament was debating a bill on patent law and public health called the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Bill 2013. It is said that the legislation gives Australian governments greater powers to exploit patents without authorisation from the patent owner via stronger provisions for Crown use and compulsory licensing. Perhaps something more along the lines of what Thailand enacted in 2007. Thailand played the global system to their advantage, exploiting a clause in the 1995 World Trade Organisation agreement on intellectual property that gives governments a large amount of freedom to bypass patents on drugs if they face any kind of health crisis.

Begging the question; in this day and age — aren’t we always under a health crisis? Whether it be from the scourge of tropical diseases in developing countries or the rise of affluent afflictions like heart disease and cancer.

Recently, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that the bill was likely to pass. Going further to state that this would allow Australia to export generic versions of patented drugs to developing countries to tackle outbreaks of diseases such as malaria, HIV and TB. Perhaps becoming the second “pharmacy of the developing world” alongside India. It seems the right balance was achieved between helping people in poor countries and safeguarding intellectual property.

There is another side to outwardly-looking medicine laws in a country. And that is the inwardly looking.

Australia has a drug subsidy scheme, that provides subsidised prescription drugs to residents of Australia — ensuring that all Australians have affordable and reliable access to a wide range of necessary medicines. The scheme has come under some recent controversy.

In 2011 and in 2012, the number of new medicines placed on the nation’s drug subsidy scheme was the lowest seen in two decades. This drop, despite no reduction in new therapies being proposed but just because of a higher rate of rejection by the advisory committee in charge of approving subsidies.

The drop brings up the question of where does this leave patients? With the scheme put in place to ensure that even the poorest of patients can get life-saving medicines the whole “Access to Medicines” debate is revisited. In this case, a slightly shifted one than the usual Big Pharma profit story. Numerous examples exist where the inability to get drugs directly influences patients.

In the ever-increasingly complicated world of drugs, medicine, and economics… the right to a healthy well-being is also being tested.

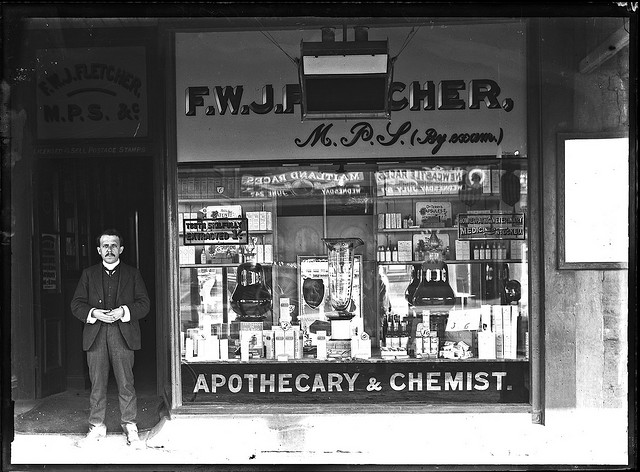

Image — source

Follow

Follow