Montaigne and the Double Meaning of Meditation

“There is no exercise that is either feeble or more strenuous … than that of conversing with one’s own thoughts.”

“We all have the same inner life,” beloved artist Agnes Martin said in a wonderful lost interview. “The difference lies in the recognition. The artist has to recognize what it is.” But in an age where we compulsively seek to optimize our productivity, the art of presence with and recognition of our inner lives, while infinitely more rewarding, is one fewer and fewer of us are able or willing to master. Of those who seek to cultivate it despite the cultural current, many turn to meditation. And yet meditation itself has an ambivalent history that reflects this tug-of-war between productivity and presence.

Among the timeless trove of musings collected in his Complete Essays (public library; public domain) is the following passage Michel de Montaigne penned sometime in the second half of the 16th century:

Meditation is a rich and powerful method of study for anyone who knows how to examine his mind, and to employ it vigorously. I would rather shape my soul than furnish it. There is no exercise that is either feeble or more strenuous, according to the nature of the mind concerned, than that of conversing with one’s own thoughts. The greatest men make it their vocation, “those for whom to live is to think.”

“Meditation,” here, is taken to mean “cerebration,” vigorous thinking — the same practice John Dewey addressed so eloquently a few centuries later in How We Think. This conflation, at first glance, seems rather antithetical to today’s notion of meditation — a practice often mistakenly interpreted by non-practitioners as non-thinking, an emptying of one’s mind, a cultivation of cognitive passivity. In reality, however, meditation requires an active, mindful presence, a bearing witness to one’s inner experience as it unfolds. In that regard, despite the semantic evolution of the word itself, Montaigne’s actual practice of meditation was very much aligned with the modern concept and thus centuries ahead of his time, as were a great deal of his views.

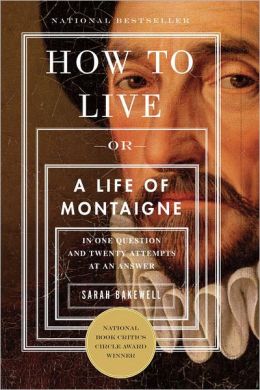

In How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (public library) — that remarkable distillation of timeless lessons on the art of living from the godfather of “blogging,” explored more closely here — British philosophy scholar Sarah Bakewell points to Montaigne’s oft-quoted aphorism — “When I dance, I dance; when I sleep, I sleep.” — noting that he “achieved an almost Zen-like discipline” and remarking on his “ability to just be,” the essence of meditation:

It sounds so simple, put like this, but nothing is harder to do. This is why Zen masters spend a lifetime, or several lifetimes, learning it. Even then, according to traditional stories, they often manage it only after their teacher hits them with a big stick — the keisaku, used to remind meditators to pay full attention. Montaigne managed it after one fairly short lifetime, partly because he spent so much of that lifetime scribbling on paper with a very small stick… Observing the play of inner states is the writer’s job. Yet this was not a common notion before Montaigne, and his peculiarly restless, free-form way of doing it was entirely unknown.

Meditation, then, isn’t merely the product of solitude — that increasingly endangered art of learning how to be alone — but is also aided by an active record of one’s inward gaze, the very practice that makes keeping a diary so spiritually and creatively beneficial, particularly for writers.

Follow

Follow