The animal link to sleeping sickness

As with many parasites, the nuisance they bring is partly compensated for by new insights they provoke. The African trypanosome is perhaps unique among all of the diseases of developing worlds. The diseases of sleeping sickness, inflicted on man and cattle alike, perhaps drove early man ‘out of Africa’ — in an attempt to avoid tsetse infested areas of the Rift Valley. The Zulu word for powerlessness and useless, “N’gana”, describes the disease in cattle — listlessness, emaciation, hair loss, and progressing towards being fatal.

Human African Trypanosomiasis, a disease David Livingstone initially linked to the bite of the tsetse fly because the cattle on his expedition died, is one of the many “tool-deficient” tropical diseases. Despite this, unprecedented progress has been seen over the past few years, according to the WHO. Today there is an upbeat picture painted of the disease burden in humans. Since 2009, the number of new cases in humans, for the first time in 50 years, has been fewer than 10 000. That is a 72% decrease in the last 10 years alone. This gain in momentum over the decades has lead those involved to think of one thing — elimination and eradication. Whispers on the lips of many are now full-throated calls to action. The worry has always been that the official numbers perhaps aren’t the entire picture, with many more cases going unreported.

It seems now there may be another threat to eradication efforts. Namely, the potential for animal reservoirs to maintain and cause a resurgence of the disease. New research published in PLOS Computational Biology uses a mathematical model to show that the West African form of the disease not only can persist in an area even when there are no human cases, but probably requires the presence of infected wild animals to maintain the chain of transmission.

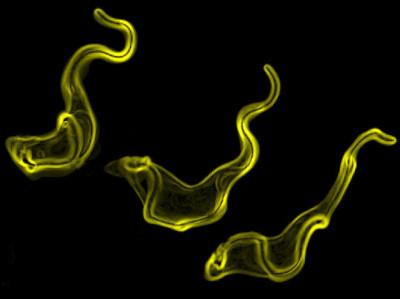

The problem is an unusual puzzle. T. brucei rhodesiense is the animal form of the disease, while the more chronic west African form, caused by T. brucei gambiense, is the cause of the human form of the disease that accounts for around 95% of reported cases. Gambiense trypanosomiasis has been found in domestic and wild animals. Whether this source of the disease serves as a significant form of transmission to humans is the question.

On the small island of Bioko in Equatorial Guinea, trypanosomiasis has been eradicated. The last case of Gambiense was 18 years ago. But, curiously, the parasite has been detected in flies that inhabit the island. The simplest explanation is that animals are no more than an inconsequential dead-end host. But how did the human parasite get there without any human cases to spread it to animals? It means that the parasite is still within the animal population. Existing as a low-level animal reservoir. And this is the most threatening fact of all — forewarning the possibility of igniting the disease again in humans — possibly jeopardising eradication efforts.

What researchers tried to do was to try and quantify the contribution of the different species to the circulation of the parasite. They took, as their sampling population, Bipindi in Cameroon. A well-known location where both animal and human case data could be collected.

What they found was that animals do play a part in maintenance of the disease, finding indications of independent transmission cycles in animals. The implications are plain — that a risk of reintroduction from animal into human populations would still be possible even when the disease was eliminated from human populations. The author’s write “…this study offers an attractive explanation for the mysterious disappearance and re-activation of gambiense foci throughout Africa.” Indeed, the decline of Gambiense sleeping sickness across much of West Africa might be mainly, and simply, down to reduction in wildlife populations, and further efforts on the disease must take into account the wild animal populations.

It’s a study that is fascinating and one that definitely warrants further research. This animal link has, for the most part, up until now, been largely sidelined. The effort to reducing human cases will continue and no doubt be amplified. The question that remains to be seen is if animal cases are a big enough threat to make an impact on the human eradication.

Follow

Follow