Bacon Fans United: The Pig Genome Sequenced

Breeding healthier and meatier piggies has been one of the many scientific challenges of the past decades; creating more reliable models to study human diseases is another. The swine disease model is indeed much better to use when studying human disorders than the (thus far) widely used murine models. Although pigs reproduce slower than mice and are more expensive to take care of, they are more similar to humans when it comes to anatomy and physiology. These common grounds have allowed the development of accurate swine models for diabetes, cystic fibrosis or retinitis pigmentosa (a cause of blindness). In its issue of 15 November, Nature published the fully sequenced and annotated pig genome. This is a major achievement, and will allow considerable progress to be made on both the yummy and the healthy fronts.

Sus scrofa domestica, by its official name, originates from South-East Asia and then went on a visit to Europe. A closer examination of the sequenced pig genome consistently shows a clear and deep split between Asian and European wild boars rooting some 1 My ago. More precisely, the analysis allowed to date the split between the two lineages in the mid-Pleistocene (1.6–0.8 My ago), a divergence the authors explain with possible colder climate prompting isolation between populations across Eurasia.

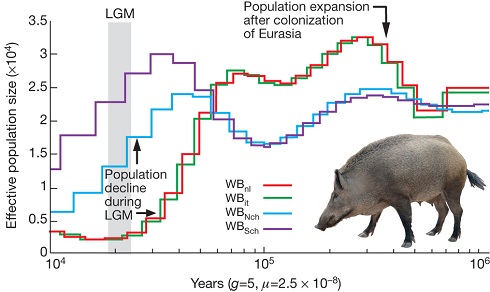

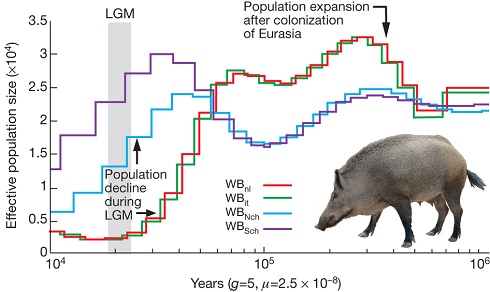

As the authors explain it:

Our demographic analysis on the whole-genome sequences of European and Asian wild boars revealed an increase in the European population after pigs arrived from China. During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM; ~20,000 years ago), however, Asian and European populations both suffered population bottlenecks. The drop in population size was more pronounced in Europe than Asia, suggesting a greater impact of the LGM in northern European regions and probably resulting in the observed lower genetic diversity in modern European wild boar.

Noticeably, pigs have been faithful companions to humans for 10,000 years now. Breeding piggies and selecting for some particular features of theirs has had an important impact on the swine genome. Authors thus identified a wide range of genes and gene families to have undergone fast-paced evolution. Immunity-related genes, already known to be actively evolving in Mammals, were for instance part of this subset, and further analysis revealed evidence for specific gene duplications and gene-family expansions. Lastly, a significant expansion of the porcine olfactory receptor gene family was described. The authors explain it by the importance smell has for pigs when scavenging for food.

—

Follow

Follow