Charles & Ray Eames’ A Communications Primer Explains the Key to Clear Communication in the Modern Age (1953)

You might think that a movie about information from 1953 couldn’t possibly be relevant in the age of iPhone apps and the Internet but you’d be wrong. A Communications Primer, directed by that power couple of design Charles and Ray Eames, might refer to some hopelessly quaint technology – computer punch cards, for instance – but the underlying ideas are as current as anything you’re likely to see at a TED talk. You can watch it below.

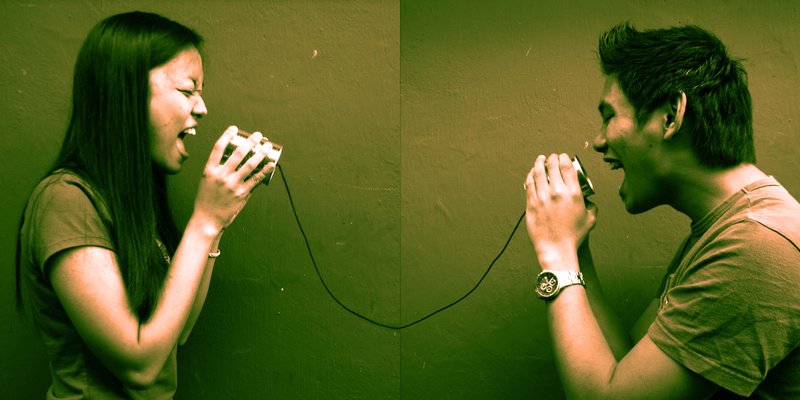

In fact, the film made for IBM was the result of the first ever multi-media presentations that Charles Eames developed for the University of Georgia and UCLA. Using slides, music, narration and film, Eames broke down some elemental aspects of communications for the audience. Central to the film is an input/output diagram that was laid out by Claude Shannon, the father of information theory, in his 1949 book, The Mathematical Theory of Communication. As the perhaps overly soothing narrator intones, any message is transmitted by a signal through a channel to its receiver. While in the channel, the signal is altered and degraded by noise. The key to effective communication is to reduce “noise” (construed broadly) that interferes with the message and to generally simplify things.

The issue of signal vs noise is probably more relevant now in this age of perpetual distraction than it was during the Eisenhower administration. Every email, text message or Buzzfeed article seen individually is clearly a signal. Yet for someone trying to work, say on an article about a short film by Charles and Ray Eames, they are definitely noise.

The Eames use the terms “signal,” “noise,” and “communication” quite broadly. Not only do they use these terms to describe, say, a radio broadcast or a message being relayed by Morse code but also the creation of architecture, design and even visual art.

The source of a painting is the mind and experience of the painter. Message? His concept of a particular painting. Transmitter? His talent and technique. Signal? The painting itself. Receiver? All the eyes and nervous systems and previous conditioning of those who see the painting. Destination? Their minds, their emotions, their experience. Now in this case, the noise that tends to disrupt the signal can take many forms. It can be the quality of the light. The color of the light. The prejudices of the viewer. The idiosyncrasies of the painter.

Of course, a painting – or a poem, or a film by Andrei Tarkovsky – is a different kind of signal than an email. It’s message is multilayered and multivalent. And while a generation of cultural theorists would no doubt chafe at Eames’s reductive, Modernist view of art, it is still interesting to think of a painting in the same manner as smoke signals.

The film’s narrator continues:

But besides noise, there are other factors that can keep information from reaching its destination in tact. The background and conditioning of the receiving apparatus may so differ from that of the transmitter that it may be impossible for the receiver to pick up the signal without distortion.

That’s about as good a description of cable new pundits as I’ve ever seen.

Follow

Follow