No Place to Go But Up

ad•ap•ta•tion [ad-uhp-tey-shuhn] – a form or structure to fit a changed environment

“The most powerful natural species are those that adapt to environmental change without losing their fundamental identity which gives them their competitive advantage.” – Charles Darwin

A few weeks ago, I stepped out on a drizzly, dreary Friday morning in Brooklyn, NY, headed to the climbing gym. Brooklyn Boulders is hosting its first ever Adaptive Climbing clinic, the brainchild of the effervescent and incredibly equipped, Kareemah Batts. I volunteered for the event, a little unsure of what to expect.

Adaptive Climbing was a 2-day event that allows amputees to experience the exhilaration of indoor rock climbing, whether for the first time ever, or the first time after receiving their prosthetics. Kareemah, herself an amputee, started climbing after attending a week-long climbing school in Colorado, sponsored by the organization First Descents, with 11 other cancer survivors and fighters. Kareemah was the only physically disabled member of the group, but walked away from that empowering event with the thought that, “If I can do this, do what they do, then I can do anything.”

She tried a number of different adaptive sports but nothing made her feel like climbing. “I fight gravity every day, and when you reach the top of a crag, send a route, it feels like you won some sort of battle or war with yourself and with the world. Climbing is the last sport that anyone would assume a disabled person would want to do or be able to do from my experience.” Kareemah specifically sought out to create an event in New York City so that others could find this same sense of accomplishment and empowerment that she had gained from rock climbing. To do this, she enlisted the assistance of Ronnie Dickson – pro-amputee climber and himself a prosthetist – through a climbing video he did with Louder Than 11 Productions. She was inspired to learn more – learn how an amputee climbs. They met in person at a climbing event in Kansas City, MO, in June of 2011. By October, Kareemah was climbing outdoors in the famed climbing sanctuary, The Gunks, in upstate New York.

Together, Kareemah and Ronnie assembled 31 participants and 35 volunteers. As a volunteer, I was blown away by the sheer determination, attitude, and strength of these athletes. Yes, they are all athletes in my book.

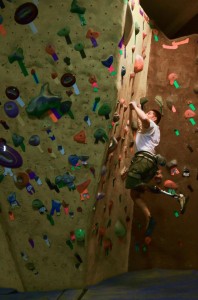

The cavernous climbing gym, converted from an old warehouse, soon swells with participants, volunteers, backpacks, loads of gear, music and voluminous good cheer. Climbers of all ages, ranging from 14-61, prepare to tackle the wall. A few participants are double amputees. When you think about climbing, you have to think of climbing with your legs, otherwise your arms can easily tire. But some of these guys just powered through it…all arms. And that was a lesson in adaptation. Finding a way to get up that wall.

You can check out some video highlights from the climbing clinic here:

Adaptive Climbing Clinic at Brooklyn Boulders

I learn even more about these incredible athletes before the climbing gets underway when I meet Barbara Evans, northeast regional chapter director for the Challenged Athletes Foundation. We immediately strike up a conversation about running, another of my own sporting hobbies. I enquire if she is at all familiar with Össur, a medical device company that designs and manufactures braces and prosthetics. “You are not a pro athlete without an Össur,” Barbara tells me. “They are a huge sponsor of ours.” I’m intrigued. She tells me about Sarah Reinertsen, the first female amputee to complete the Ironman World Championships in Kona, Hawaii. She contacted Össur and wanted to know why her prosthetic didn’t have grip or traction like a running shoe. They told her to contact Nike…and the Sole was born.

This leads me to thinking how far the technology of prosthetics has come; how designs have been adapted for just about any situation or sport you could think of. No two people had the same prosthetic; some seemed to blend fluidly with the climber, with even the knee bending, while other prosthetics were immobile. This leads me back to Össur, so I contact my friend Katie Swanson who works in their Seattle office. She tells me Justin Pratt is the guy to speak to and when I interviewed him the following week, I am awed by the engineering ingenuity of passionate and purposeful design.

Justin is the national clinical manager – bionics, for Össur and has 18 years’ experience in the prosthetics industry. He provided an overview of the advances in prosthesis technology over the last 10-15 years. Early prosthetics consisted of a low-tech metal leg, for instance. Today, many prosthetics have incorporated the light-weight material of carbon fiber. When you get into the high-end range of prosthetics, we are not talking about a device to merely give the appearance of a leg. We are talking about a mechanical device to “replace and replicate” the actions of a leg or an arm.

Össur in particular has improved the manufacturing of prosthetics with carbon fiber layering, increased energy storing, adding vertical shock and rotational components. They use software and microchips and load sensors to determine how a patient is using the prosthesis; for instance, how they stand on it, how much weight they place on it. Think of it like a digital scale. By being able to determine how much weight is distributed on the prosthetic, this can help customize the technology to the athlete’s biomechanics and improve performance.

But performance is based on maintenance. The average lifespan of a prosthetic is 5 years. It is a mechanical device and requires service, as would a car. Considering professional runners and triathletes are training 50-60 miles a week, maintenance of the prosthetic is important. If a person is not so aggressive in their daily use, prosthetics could last 7-10 years. A runner typically has designated shoes for running and shoes for wearing to the office. Similar for climbing or any other sport, there are designated prosthetics athletes use for competing in their chosen events.

I asked Justin what he found most inspirational about his work – In his own words… “It may sound cliché, but this work is actually changing somebody’s life. From the very first moment they receive the prosthetic, it’s life-changing for them. An amputee will describe this as the closest they’ve ever been to death. And you have the tools to bring them back – it’s priceless. Giving someone a new outlook on a catastrophic event in their life. You’ve made a difference in their life – not just with the prosthesis – it’s coaching them, counseling and motivating them to keep going. But the best outcome will only come if you have the best patient in the world, and likewise you need the best prosthetist. You strive to get back what they have lost.”

Looking back on that day at the climbing gym, there were no boundaries in sight. As Ronnie said, “most people come to find that the only boundaries they have are the ones they set for themselves.” There were walls to climb, heights to ascend. It’s an enlightened outlook to have in life: plan a route, adapt and overcome the obstacles along the way.

Follow

Follow