From fables to Facebook: Why do we tell stories?

Throughout human history, stories have existed across all cultures in all forms, from ballads, poems, songs to oral history, plays, novels. Some narratives have evolved along with the human species—we are consistently drawn back to ancient parables, fables and fairytales, constantly reworking them into modern contexts.

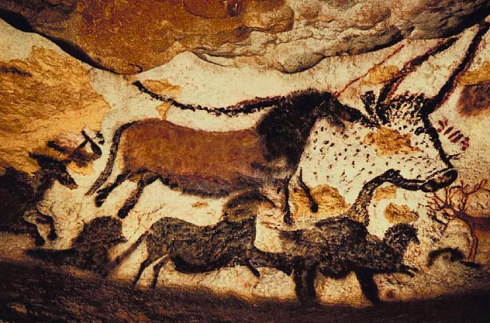

Narrative is a gift unique to the human species, but how as it survived for so long? Is it a by-product of evolution or essential to survival? What drove us to painstakingly inscribe portraits on rocky walls in ochre and charcoal, to compose and listen to lengthy ballads of heroes’ tales, to nosily read people’s Facebook statuses about their day, to devour novels and films like we’re hungry for fictional worlds? Neuroscience and developmental psychology have begun to answer these questions, embarking on the ambitious task of explaining why we tell stories.

Storytelling is one of our most fundamental communication methods, for an obvious reason: narrative helps us cognise information. Telling intelligible, coherent stories to both ourselves and others helps our brains to organise data about our lives and our world. But when we ask why stories are so effective at helping us cognise information, the answers are surprising: it seems that somewhere in the otherwise ruthless process of natural selection, evolution has wired our brains to prefer storytelling over other forms of communication.

Good stories engage us. When we hear plain, bloodless facts, the language processing centres of our brain light up and we decode words into meaning—but when we’re told a story, not only are language processing centres lit up, but also a vast array of other regions distinct from those centres. For example, if you tell a friend a story about a dinner party at which you ate delicious roast pork, their sensory cortex will light up; or if you tell them about the game of football, their motor cortex will become active. The parts of the brain they would use if actually experiencing the event light up, even though they are only being told about it.

This is particularly interesting when considering the effect that literary techniques have on our brain activity. In a 2006 study published in NeuroImages, Spanish researchers asked participants to read both neutral words (such as chair and key) as well as words with strong odour associations (such as coffee, perfume, lavender and soap). Brain scans using an fMRI machine showed that when they read the odour-associated words, their primary olfactory cortex lit up; but when they read the neutral words, that region remained dark. In another study at Emory University, texture metaphors such as “the singer had a velvet voice” or “he had leathery hands” roused both language processing areas and the sensory cortex, while more factual statements such as “the singer had a pleasing voice” only roused language processing areas. Similarly, statements like “he kicked the ball” caused activity in the motor cortex—and in different parts of the motor cortex, depending on which body part was described.

(Interesting side note: our brain actually learns to ignore certain phrases that were once evocative—the term “rough day,” for example, is often treated simply as words and nothing more, because for some it can no longer activate the sensory cortex.)

It seems, therefore, that narrative language and literary techniques can stimulate the entire brain, which is why storytelling can make us feel alive, as if we’re really in the action. This thorough mental immersion shows that our brain, at least, doesn’t make much distinction between reading about something and actually experiencing it.

Evolutionarily speaking, how have we made use of this? The answer may lie in the way stories inherently present conflict.

Keith Oatley, professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Toronto, has proposed that due to our lack of neurological distinction between fictional and real experiences, stories can produce a vivid simulation of reality in our minds. Stories can give people experiences they can’t have in real life, such as how novels give full access to another person’s emotions and thought processes—as well as situations that would be dangerous or problematic in real life. Fiction plunges us into intense situations that we see parallels of in our own lives, acting as flight simulators and preparing us to deal with similar problems in real life.

At their very simplest level, stories are told in the way that our brains are wired: cause and effect. We constantly think in narratives—if we do this, then this will happen—whether we’re thinking about buying groceries or seducing our neighbour’s husband. We’re constantly playing out scenarios, and storytelling allows us to simulate these scenarios and determine cause and effect without having to deal with the real thing.

Older stories, myths and parables are rich with morals, preaching to their audiences to not give into temptation, to not trust liars, to not underestimate others, not to eat those juicy-looking berries because did you hear about your great uncle John who died from eating just a single one…and these have served an important societal and evolutionary function: audiences learned how to avoid such situations without ever having to experience them.

“Just as computer simulations can help us get to grips with complex problems such as flying a plane or forecasting the weather,” Dr. Oatley notes, “so novels, stories and dramas can help us understand the complexities of social life.”

The evolutionary mystery of storytelling isn’t solved yet, but there’s some interesting evidence for identifying a prime suspect.

Fuge L (2013-06-18 00:33:20). From fables to Facebook: Why do we tell stories?. Australian Science. Retrieved: Jul 19, 2025, from https://ozscience.com/psychology/from-fables-to-facebook-why-do-we-tell-stories/

Follow

Follow

2 thoughts on “From fables to Facebook: Why do we tell stories?”

Comments are closed.