Predicting the next epidemic

In some parts of this world the rains predict disease, and a hot, dry, dusty wind is the harbinger of a meningitis outbreak that is yet to come. Now, from where you sit, Google will soon predict the next great epidemic.

At this time of year, ever since that 2009 paper was published on flu trends, seasonal influenza and how we predict it, is a recurring topic.

It seems we are always moments away from the next great flu epidemic. This year saw a novel coronavirus make the rounds. A virus that usually causes nothing more serious and common than a cold, was the source of severe respiratory illnesses in the Middle East, with reported cases coming from Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Jordan, and resulting in 5 fatalities.

The curious case of the novel coronavirus is a new strain of virus that has not been previously identified in humans. The hypothesis is that it jumped the species barrier, but, as of yet, a definitive origin has not been identified.

When a disease will decide to jump the species barrier is hard to predict. Some of the most serious afflictions of humans in recent times have had their origin in animal diseases. HIV/AIDS and ebola being the prime example. Seasonal influenza is another — causing tens of millions of respiratory illnesses and up to half a million deaths worldwide each year.

In mankind’s eternal struggle against disease, as the adage goes, prevention is better than a cure. But how do we prevent disease? How do we mitigate for an oncoming plague or pestilence? A part of this prevention is predicting it.

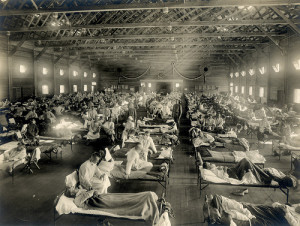

Currently, we can only really predict an epidemic when it is currently in motion. Hospitalizations are the only way we can really track a disease. When it is possibly already too late. When people are already sick.

In the week the world was supposed to end, the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) released its weekly report on influenza surveillance, like it had done since week 40 of this year. The report aggregates data on influenza-like illnesses reported in primary health care facilities, as well as virological and clinical data.

Flu surveillance, in Europe and similarly in the US, is based on nationally organised sentinel networks of physicians, mostly general practitioners (the first person you go see when you’re ill), covering at least 1 to 5% of the population in their countries. Each sentinel physician reports the weekly number of patients seen with influenza-like illnesses and acute respiratory illnesses.

The report is essentially there to tell us when a flu epidemic is going to break out. In week 49, ECDC announced that the season of influenza transmission had begun.

Along with the direct methods of detecting and monitoring disease, in recent years new and innovative non-direct methods have been tested. From sales of over-the-counter medication to online activity. The idea is to try and record health-seeking behaviour… ie before the disease has taken hold in a population.

Monitoring disease, 140 characters at a time…

Flu is a disease very amenable to being searched and turning up in social media. Health-seeking behaviour — in this day and age, we google every ailment. However, diseases which are more serious probably won’t follow this social pattern.

The concept is essentially trying to “predict the present”. Google flu trends isn’t the only one to mine social data. Mappyhealth mines twitter data, tracking 25 conditions from around 200 health related terms. Searching for the spikes in activity from those certain key terms. Spikes in activity above the social noise, pointing to a significant event associated with the term. In some places it has been shown to be a good indication of the real underlying movement of disease.

But what of diseases that are not as commonplace as the flu? How would google or twitter act as an early warning system for diseases of a tropical nature?

2.5 billion people are living in areas at risk of Dengue fever, otherwise known as breakbone fever — a painful and sometimes fatal viral disease characterized by headache, skin rash and debilitating muscle and joint pains. In some cases, it can lead to circulatory failure, shock, coma and death. There are up to 100 million infections a year — and it’s growing. Incidence and geographic distribution of dengue has gone up in many countries, spurred on by a changing climate.

So how do we predict a disease that is more complicated than simple person to person transmission? What if there is another step to overcome — namely, in the case of dengue, a mosquito? Early warning systems for vector borne diseases are incredibly complex.

Google Dengue aims to do the same thing flu trends did. And the results are remarkably similar. Google search volume for dengue-related queries were able to adequately estimate true the dengue activity and official reported cases. The realisation that disease can be tracked in this manner is a relatively new occurrence. Few have explored non-traditional settings for monitoring epidemics, dengue or otherwise.

The caveat, however, is obvious — a term turning up in a search term doesn’t necessarily point to the presence of the disease. “Now-casting” (as opposed to forecasting) using a web-query based surveillance depends on a few crucial factors. First and foremost is the evident internet availability — and in developing countries this might prove difficult.

Despite its limitations (panic-induced searching from the announcement of a novel outbreak, backed up by media sensationalism), it proves effective and, most importantly, low cost. Up-to-date and accurate estimations of disease lets the health professionals make an effective response to the moving disease. In the case of influenza, where a vaccine is available, it makes sense. In the case of dengue, all that remains is a working vaccine for this method to live up to potential.

Follow

Follow

1 thought on “Predicting the next epidemic”

Comments are closed.