The beat the mosquito’s heart didn’t skip

It pulsed continuously without stopping. Then it repeated, as it had done many times before. Then, without delay, almost without skipping a beat, it changed direction. The action was as old as man himself, yet this time, completely and uniquely different — the perfect heartbeat. The perfect mosquito heartbeat.

An interesting quirk of nature is how remarkably constant the number of heartbeats exist within a lifetime. An interesting quirk, more a function of the metabolic demands of the animal in question rather than any underlying feature of the heart itself. Humans, mice, insects all have the same number of total heartbeats. The human heart, from life to death, will beat roughly 3 billion times. A mouse will use up its heartbeats in about two years. An elephant, with a much slower heartbeat, will last for much longer. The mosquito’s heart beats at a rate of just over one beat every second (1.3 Hz). In one minute it will beat 82 times, of which, some of that will be in the other direction.

The heartbeat is nothing unique to humans and has been around long before us, but we have romanticised it and given it a meaning more than its basic function. For researchers at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennesee, this is also the case for the mosquito’s heart, where function and meaning is more than its basic, simple architecture.

Dr Julian Hillyer, the lab’s director, and his team have offered the most comprehensive visualisation to date of how the mosquito’s heart beats. They filmed live restrained female Anopholese mosquitoes — the same species of mosquito responsible for life threatening malaria — through a microscope connected to a very sophisticated camera.

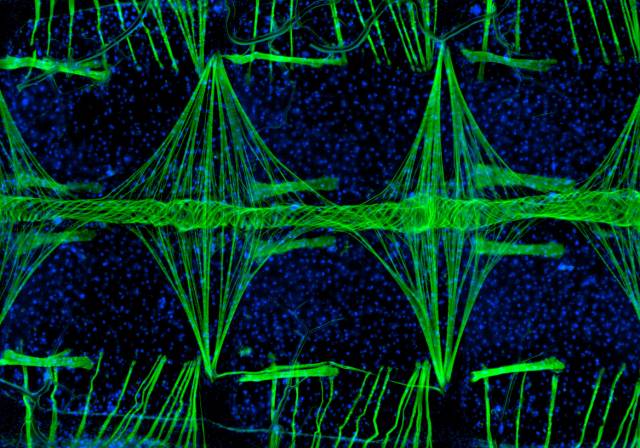

The beatings of thirty mosquitoes were collected and analysed frame-by-frame to arrive at a comprehensive structure of the heart. They painstakingly dissected individual mosquitoes, injecting infinitesimally small amounts of fluorescent fluid into the mosquito, allowing them to describe the mechanics, directionality and flow involved when the insects blood (hemolymph) is propelled through the heart.

A mosquito’s heart is very different — without veins or arteries, it pumps a clear liquid called hemolymph. The hemolymph flows from the heart into the abdominal cavity and eventually cycles back through the heart. The heart runs along the insects body as an unbranched tube, no thicker than three tenths of a millimeter. Helical twists of muscle fibres support the central tube. Their sequential contractions makes the heart in a wave-like peristaltic action. A peristaltic action that has the ability to run in both directions.

Another set of muscles anchors the heart where ever there is a valve, at intervals, along the mosquito’s body – just underneath its cuticle shell. All of this was visualised in fluorescent detail, using different coloured flourescent dyes to highlight different structures inside the insect’s body. Winning the lab’s images the Nikon Small World photomicrography competition in 2010.

As stunning as the images were, it was the functionality gained from the study that provided the most insight. Following and tracking tiny microscopic particles (microspheres) showed how the insect’s hemolymph entered and was expelled from the heart, and, most importantly, how the heart reverses direction.

Most of the time, the heart pumps the mosquito’s clear hemolymph blood towards the mosquito’s head, but occasionally it reverses direction and pump fluid to the last segment of its abdomen. The direction in which the heart contracts reverses roughly 5 times every minute.

Heartbeat reversal is not unique to the mosquito — a phenomenon that has been observed in other orders of insects. You would think that something that small would have no need for such an elaborate beating system, but perhaps it is the only way the heart can regulate the different hemolymph pressure and volumes entering it. Thus far, a conclusive “why” has eluded researchers.

An insect group that carries malaria, the virus that causes dengue fever, West Nile virus and the lymphatic filariasis causing nemetode roundworm Brugia malayi. Mosquitoes represent the most significant pests and disease vectors that transmit deadly human and animal pathogens.

The insect heart is the gateway to the insect’s circulatory system and to understanding the interaction between the insect and its pathogens. Dr Julian Hillyer and his team have turned their efforts to the mosquito’s immune system, hoping to understand the process in which pathogens migrate through the mosquito’s body cavity and the mosquito’s own immune system response against them during their journey to their mouthparts — the point of entry relevant to human disease.

Certainly, a better understanding of its biology will be needed to contribute to the development of novel pest and disease control strategies as diminishing efficacy of current control methods continue to cause problems. A increasing realisation that tackling the disease before it gets into man is a worthwhile effort and becoming more and more a viable option.

Follow

Follow