Talking the Language of Science

I have mentioned before that part of the reason why I like science so much is that you get to play with stuff. It might come as no surprise then that I begin each year with a game called “Mrs Spencer Says”. It’s much like Simon Says, but instead of using everyday terms for body parts I use really heavy technical medical terminology. During this game where the children try to guess what on earth a hippocampus or xiphisternum is, we talk about the nature of scientific language, its complexities and its pitfalls. It’s a tough game to decode at first. It gets better each time you play though. The language of science is exclusive and to play the game of science, you must know the language. For our children to become scientific literate beings, they must regularly and intentionally be shown how to interpret and use scientific language.

Oral language provides the basis for all forms of communication, so it is the obvious place to start learning the language of science. Babies and toddlers acquire language through experiences in their environment and through their interactions with adults. This doesn’t change. Language acquisition is experiential. In providing a variety of scientific experiences in the classroom, the children naturally talk about what they observe. When we ‘do science’, our classroom is full of chatter. At times this is teacher-led; although I always aim it to be student centred. These rich substantive conversations aid in the development of scientific vocabulary.

Through hands-on experiential science, children learn to observe and describe phenomena. There is no right or wrong. They are encouraged to use their variety of senses in observing and describing. What did you see? What did you hear? What did you feel? (We make the cardinal rule never to taste in science.) They are encouraged to talk in their group about their observations and then make some conclusions. Why did that happen? Through all this talk, children learn to examine phenomena critically and build their scientific vocabulary. It also allows them to hear and consider multiple perspectives as they examine their ideas more deeply and make greater conceptual links.

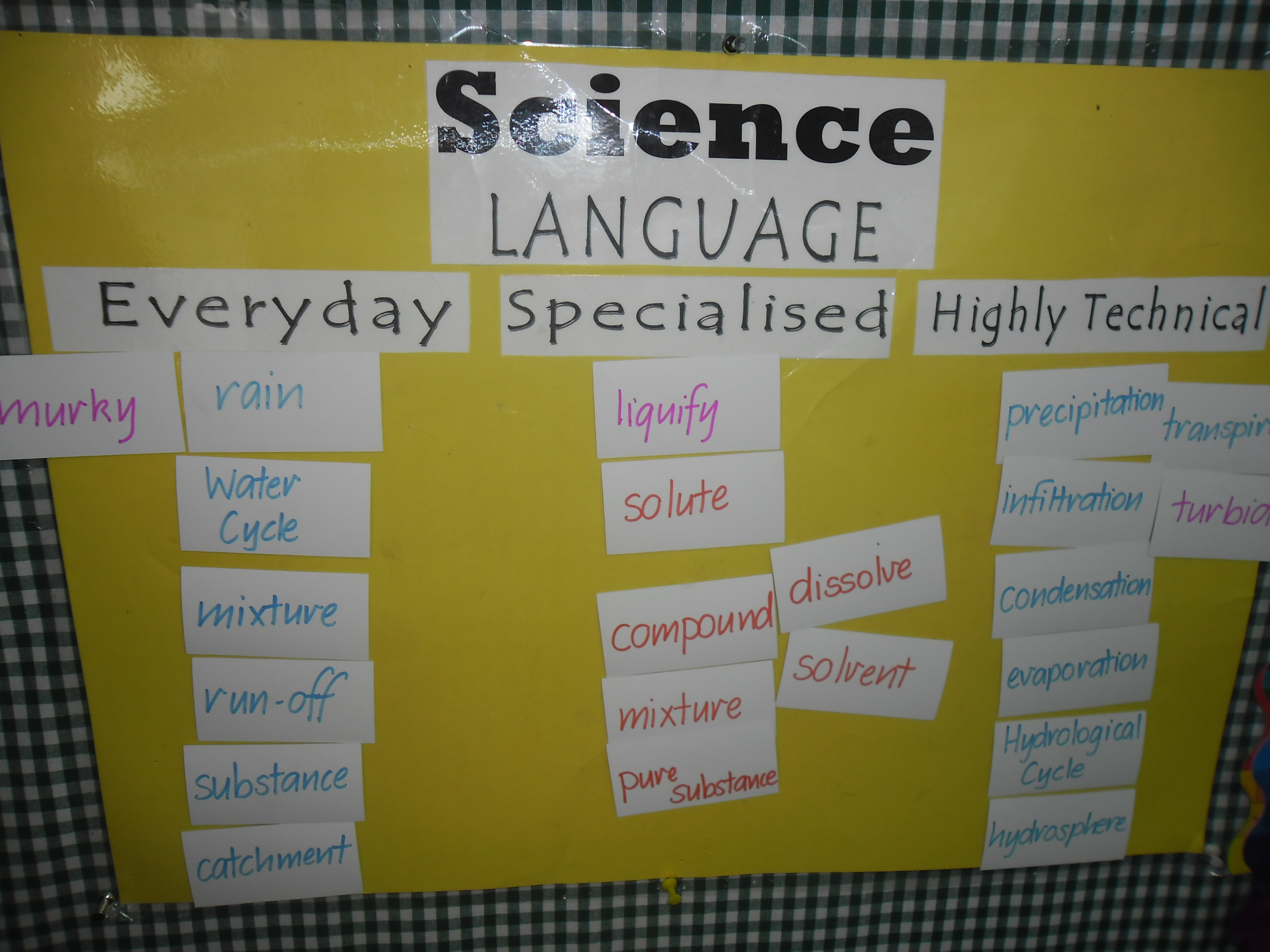

Irrespective of their age, children will have pre-conceived scientific ideas and their own explanations for ‘how things work’. Quite commonly in the initial stages of a particular unit, children use everyday terminology to describe their observations. In building field knowledge it is important to start at the level of children’s understanding and vocabulary. Through guided questioning, directing conversations and effective modelling of scientific language even quite young children will begin to use the highly technical vocabulary specific to the field of study. I ask the children to think, talk and write ‘like a scientist’. Take for example; when a child describes a solution as ‘murky’, we brainstorm together how a scientist might describe this. If necessary, I will give them the correct word or a selection of words. When we examine ‘murky’, we can differentiate between turbidity and translucency. What sounds more like a scientist; ‘sticky’ or ‘tenacious’. To summarise the notable educational theorist Vygostky, “it is with the understanding of words that conceptual development occurs”.

The beginnings of our word wall – Grade 6/7 Water Unit.

Although scientific process words are similar across scientific domains, the learning of scientific language is difficult as each field of science or domain of science has its own vocabulary. Additionally, scientific language is also found in models, diagrams, tables and mathematical equations. Students must also have explicit instruction and practice on how to decode and use these; however the value of talk in science cannot be under-estimated.

There are numerous incidental language encounters that can occur within a science lesson. Children should be encouraged to play with the language until they are able to use it in its right context. I once overheard a group of my Grade 3 students in the playground one day deciding what game to play. One of them said, “I concur, we should play robbers.” Earlier that day I had told them that when scientists agree with each other – they would write, “I concur with —-.” Dialogue between the teacher and the children should be rich in scientific words and phrases. Besides, it is really entertaining to hear a young child trying to get their tongue around words like hypothesis and molecule.

Spencer D (2013-02-21 00:35:34). Talking the Language of Science. Australian Science. Retrieved: Jul 18, 2025, from https://ozscience.com/education/talking-the-language-of-science/

Follow

Follow

good work !!!