The extinction that is yet to come

By 2050 they will all be gone. The worst is yet to come.

The Amazon rainforest contains a wider variety of plant and animal life than any other biome in the world. The region in its entirety is home to roughly 2.5 million insect species, tens of thousands of plants, and some 2000 birds and mammals. To date, at least 40,000 plant species, 2000 fishes, 1000 birds, 427 mammals, 428 amphibians, and 378 reptiles have been scientifically classified. The Brazilian Amazon harbors roughly 40% of the world’s tropical forest and a significant proportion of global biodiversity.

The numbers speak for themselves. However, over the past few years what we’re seeing is a biodiversity crisis in slow-motion. Those numbers are at risk. The largest drivers of which being climate change and habitat loss by deforestation.

Habitat loss results in species extinction, but not immediately. When habitats shrink it may take several generations after an initial impact before the last individual of a species is gone. Extinction against the clock and in slow motion.

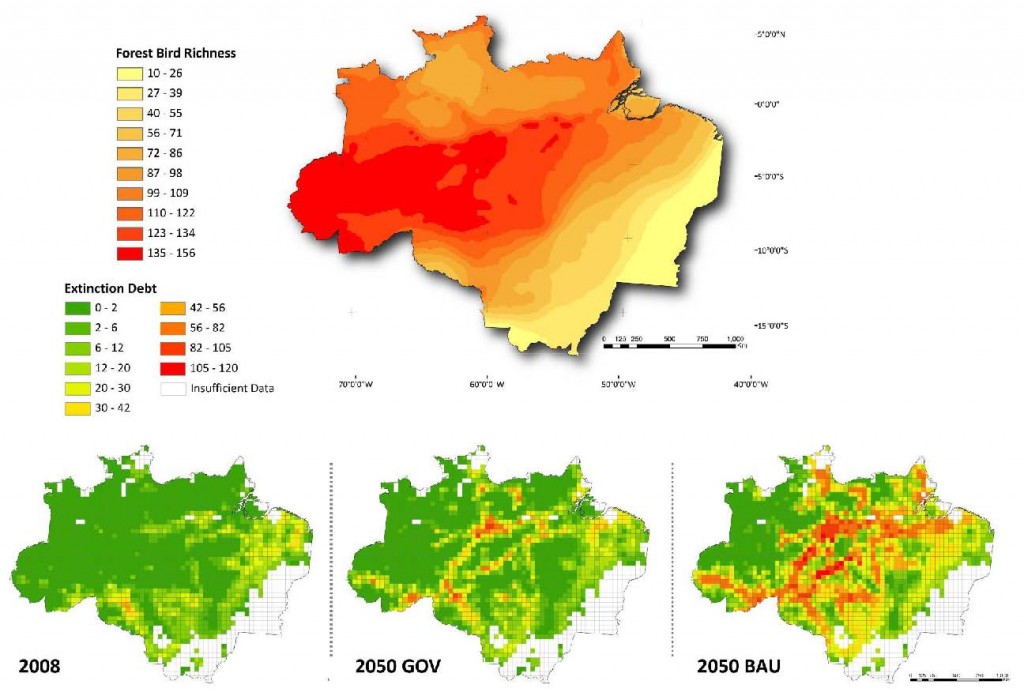

Visualising how this occurs and estimating the impact has always been a problem for researchers. The question now is — how many species are headed for extinction as a result of past and future deforestation?

New research published today in Science describes cutting-edge statistical tools used to devise a novel strategy to estimate the expected number of local species extinctions as a function of the extent of habitat loss.

Researchers made predictions on the extent of the extinction damage based on four possible scenarios — two in which all parties comply and respect current environmental law and protected area networks; and two which rely on strong reductions and eliminations in current deforestation rates. A reflection of recent pledges by the Brazilian government and potential reductions in deforestation proposed in 2009. What researchers describe is an estimation of something much more serious than previous estimates.

Deforestation over the last three decades in some localities of the Amazon has already committed up to 8 species of amphibians, 10 species of mammals, and 20 species of birds to future extinction. Local regions will lose an average of nine vertebrate species and have a further 16 committed to extinction by 2050. The worst is yet to come it seems. More than 80% of local extinctions expected from historical deforestation have not yet happened.

An “extinction debt” — future biodiversity loss which have yet to be realized as a result of current or past habitat destruction — offers a time delay, the chance to save them… but it is a race against the clock. A window of opportunity for conservation, during which, researchers write, “it is possible to restore habitat or implement alternative measures to safeguard the persistence of species that are otherwise committed to extinction.”

The fight for the heart of the Brazilian Amazon has already begun.

Brazil has a long-standing tradition of conserving its Amazon — or, at least, trying to be seen as conserving its Amazon. Up till now a mixture of firm legislation and strong-arm tactics ensured this. The Brazilian government has been known to use police raids to crack down on illegal deforesters. Currently, around 54% of Brazilian Amazon is under some form of environmental protection. Thanks, in no small part to the country’s half-century-old Forest Code.

The past few years, since the economic crisis, has seen political will erode and the Forest Code challenged. In today’s economic climate, reconciling income generation with sustainability is a difficult balance to maintain. The economist’s mantra, foregoing all for economic growth, has seen the Brazilian government pushing forth a rapid expansion of infrastructure in the Amazon, from the construction of vast hydroelectric power plants in the Amazon basin to agricultural expansions. Agriculture represents a significant proportion of Brazil’s GDP and there is pressure to open up more forest land to production.

Earlier this year, a bill seeking to overhaul the Forest Code was up for debate. As Rio+20 welcomed the world to debate the merits of development versus conservation Brazil herself was going through the same struggles.

Protected forest areas across the Brazil Amazon represents a cost of US$147 billion for Brazil (a number that includes the lost profits if they were to be opened up for a free-for-all as well as investments needed for their conservation). They cover a total area of 1.9 million km² and encompass just under half of the Amazon biome. It is hoped that this culture of conservation will continue and expand the total area.

In April of this year, the new forest code was approved, with many reservations from conservationists. The new code allows for a considerable reduction in reserve areas in the Amazon.

How this will affect the “extinction debt” is yet to be seen. Researchers acknowledge that their “best case scenario” (an end of deforestation scenario) “appeared feasible when first published in 2009 but appears much less so now in the face of recently voted changes to the Brazilian Forest Code that may weaken controls on deforestation rates.”

The future of biodiversity in the Brazilian Amazon currently stands at a critical juncture. It seems the Amazon will continue to collect extinction debt for decades to come as we witness how present-day decision making policies by governments impacts on future species extinctions.

[Image courtesy of Alexander Lees]

Follow

Follow

2 thoughts on “The extinction that is yet to come”

Comments are closed.