Is That Satellite Junk? Or An Important Piece of Australian History?

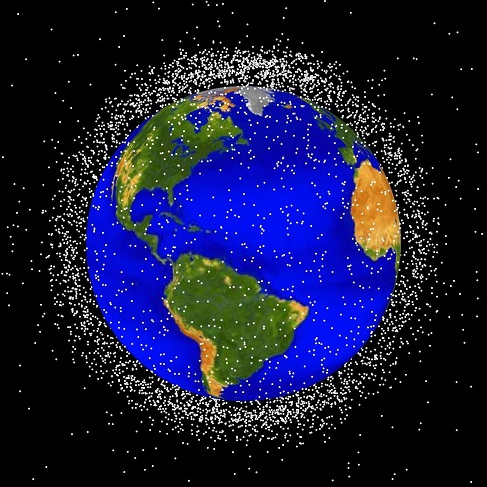

Please don’t go all Chicken Little on us, but do be aware: there’s thousands of pieces of metal orbiting above your head. Many of these satellites are dead (read: out of fuel and uncontrollable.) And if one happens to smash into another, the results could be catastrophic. Humans depend on satellites for everything from the Internet, to weather forecasts, to ATMs.

This is a growing problem that is preoccupying entities such as NASA, which has an Orbital Debris Program Office. The Europeans recently had a space debris conference where experts estimated there is 1 billion Euros of infrastructure that must be protected. They called for some sort of retrieval solution as soon as possible.

Against this backdrop stands Alice Gorman, a space archaeologist at Flinders University in Adelaide. She says she’s fully aware of the problem, but urges the relevant authorities not to take out these satellites willy-nilly. Part of Australia’s and the world’s cultural heritage rests in these bits of metal, she said at TEDxSydney last month.

“Before we start trying to get rid of some of this stuff,” she told attendees in a speech later put on the web, “[ask] does any of it any have cultural significance for us? Does it have heritage value? And do we want to do something sensible about it, instead of destroy all that without thinking?”

Australia is among the nations that could stand to lose that heritage if satellites are destroyed without forethought, she said. Among those is a satellite that was designed by amateurs and was one of the first Australian ones to make it into space.

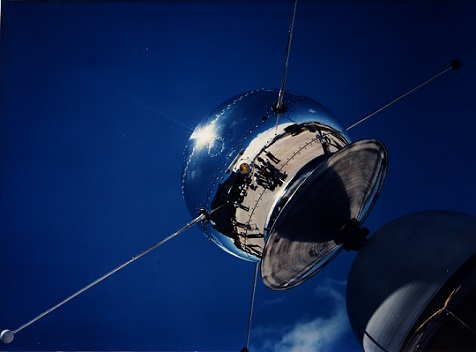

Called Australis-OSCAR-5, students at the University of Melbourne constructed the small amateur radio satellite out of whatever parts they could scrounge on a small budget. In some cases, pieces came off-the-shelf — not from satellite manufacturers, but from local stores, Gorman said. It launched in 1970 and has been dead for decades, she added, but there is still history attached with it.

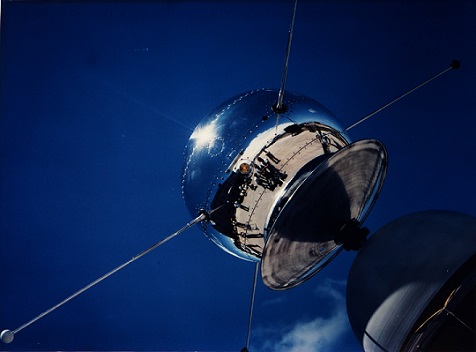

Australian ground infrastructure is also, in a way, represented in space. Vanguard 1 is the oldest human object to exist in orbit. Launched in 1958 by the United States, it signalled the country’s entry into the Space Race of competing missions that occupied Americans and Russians for at least the better part of a decade. (It came to a symbolic end when Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969, although the Russians were already pursuing other goals than moon missions by this time.)

When the United States was getting ready to lob Vanguard into space, officials approached several countries (including Australia) to set up a network to track the satellite in orbit, Gorman said.

Additionally, worldwide groups of amateurs (including Australians) were invited to send in their observations of Vanguard 1. Remember, satellites were rare machines in those days, so initiatives such as that would have gained a lot of attention.

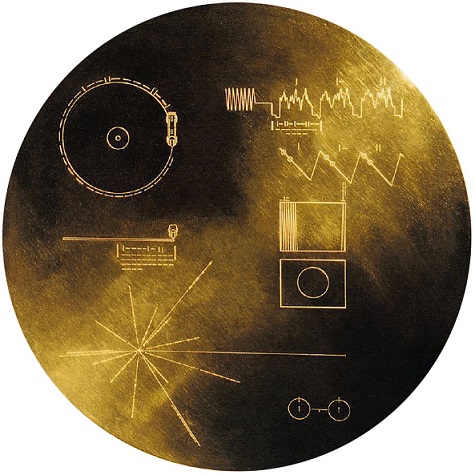

Gorman said these objects, although they haven’t been functional for years, are symbolic pieces of us in space. Perhaps the ultimate expression for Australians is the Golden Record that travelled on each of the Voyager spacecraft that are on a one-way trip out of the solar system. The sounds of Earth recorded on them include some from Australian aboriginals.

“The [spacecraft] remind us that space isn’t just empty and vast and black and dark, and somewhere else out there we’re actually part of it,” Gorman added.

“It is something we should be feeling connected with, not cut off from. Our cultural heritage — these places and these artifacts — demonstrate the kinds of attachments and meanings we can give to these space places.”

To space authorities, Gorman seems to be saying: your move. There is a need to remove objects fairly quickly and efficiently, but before doing so, perhaps their history should be taken into account.

That said, this opens up questions about how to deem one piece of debris more culturally significant than another. Perhaps an international office of sorts could be established to deal with these questions, basing its work on that of heritage organizations around the world.

Howell E (2013-06-26 00:04:04). Is That Satellite Junk? Or An Important Piece of Australian History?. Australian Science. Retrieved: Jul 27, 2024, from https://ozscience.com/space/is-that-satellite-junk-or-an-important-piece-of-australian-history/

Follow

Follow