It’s a small world after all

What we know of exoplanets has developed at the same time as the technology which we use to discover them. This is, in my opinion, the most exciting thing about the entire field of study. For instance, when we first started spotting planets around alien suns, we found huge gas giants. Hot jupiters, extremely massive and close to their parent stars. For a while, some conjectured that this type of planet may be quite common in the Universe. But since then, we’ve developed more powerful methods of searching the sky and, as it turns out, smaller planets are much more common than huge superjovian worlds. The latest piece in the puzzle comes courtesy of NASA’s Kepler space teescope. Near the end of last month, NASA announced the discovery of the smallest exoplanet ever found around a sun-like star!

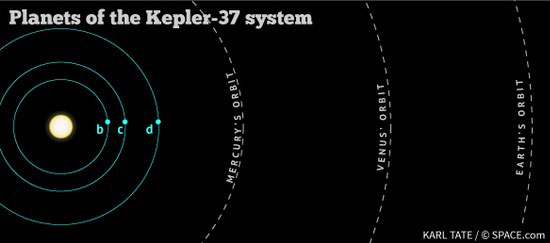

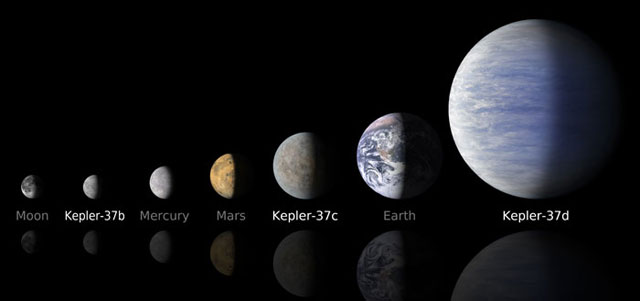

Kepler-37b really is tiny. In fact, the whole Kepler-37 system is tiny – the entire system discovered so far can fit inside the orbit of Mercury! The innermost little world is under 100th the mass of Earth, it’s expected to have a radius of around 3867 km (assuming the same average density as the planets in our own solar system) making it smaller than Earth’s moon. One can only apprehensively wonder if this will spark yet another debate over how large an object has to be before it’s considered a planet. With such a tiny orbit, it also has a year lasting just 13 Earth days. Even though the star Kepler-37 is slightly smaller and cooler than the Sun, it’s still enough to heat the surface of tiny 37b to a roasting 700 Kelvin (nearly 430°C). Needless to say, while we all like stories which talk about potential alien life, this is unlikely to be a home for any lifeforms we might recognise.

Kepler-37b is very definitely the runt of the litter. Its sibling worlds, denoted by the letters c and d, are respectively slightly smaller than Earth and about twice the size of Earth. Of course, these planets are also very close to their parent star. The interesting thing is that we’re discovering more and more small worlds around other stars. More and more exoplanet astronomers are warming to the idea that small rocky planets are likely to be the most common in our galaxy. Our current technology might have trouble spotting them further than a certain distance from their parent stars, but they’re likely to be out there waiting to be found.

Even detecting Kepler-37b was quite a notable feat. It was only possible, in fact, because of a set of rather special circumstances. The star Kepler-37 is particularly quiet, lacking the noisy sunspots and features which cause brightness variation in most stars, making it a particularly clear target. It’s also relatively bright in Kepler’s field of view.

To learn more about this star, and hence get greater accuracy on the measurement of the planets it carries in tow, NASA astronomers used a technique known as asteroseismology. Not dissimilar to the way geologists measure earthquakes, asteroseismology is the study of vibrations within a star, measured by accurately observing pulsations in the star’s surface. All stars are constantly bubbling and boiling, and this causes the whole star to vibrate at a number of resonant frequencies – soundwaves – in exactly the same way a bell vibrates when it rings. By measuring the precise frequencies of those soundwaves, a lot can be determined about the interior of a star. Incidentally, this same technique can be used to effectively “listen” to the Sun.

Interestingly, because Kepler-37 has such an eerily peaceful surface for a star, it was very easy to measure those vibrations, making Kepler-37 the smallest star ever to be studied this way. Normally, only large stars are observed using asteroseismology because the measurements need to be very precise. Conveniently though, the Kepler telescope was built for breathtaking precision.

A tiny planet discovered orbiting a singing star 215 light years away. How poetic!

Image credits:

Top – NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech

Middle – Karl Tate/ © space.com

Bottom – NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech

Hammonds M (2013-03-11 00:20:42). It's a small world after all. Australian Science. Retrieved: Feb 05, 2026, from https://ozscience.com/space/its-a-small-world-after-all/

Follow

Follow