Radio quiet, please!

Originally conceived over 20 years ago, there’s a project being undertaken by scientists and engineers across the whole world to help us all better understand the mysteries of the galaxy and the very beginnings of the Universe. It’s estimated to be completed by around 2024,costing $1.85 billion AUS (€1.5 billion). Once completed, it’s set to be the most complex and technologically advanced machine ever built by humanity. It will use enough optic fibre to wrap twice around the Earth and will need a computer capable of performing 10^18 operations per second – about three million times the number of stars in our galaxy. It will produce over 980 Exabytes of data every day (equivalent to about 15 million 64GB iPods) and to cope with that, it will need to handle data transfer rates over 10 times as high as the current global internet traffic. No, it isn’t a starship. But it might just be the next best thing.

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) is one of the most ambitious scientific projects ever devised, and when completed it will comprise a huge number of telescope antennae which will work as one to form a single radio telescope so powerful that it could detect an airport radar on a planet 50 light years away. The sensitivity of any telescope is defined by the area it uses to collect data. With optical telescopes, this is the size of the mirror, and with radio telescopes it’s typically the size of the dish. The SKA gets its name because when fully constructed, all of the detectors and antennae that make it up will have a combined area of one square kilometre, or one million square metres. To put that properly into perspective, the Green Bank Telescope is currently the largest steerable single dish radio telescope, and its area is just under 8000 square metres.

Being astronomy’s answer to the large hadron collider, the SKA is a staggeringly large international collaboration. I was lucky enough to attend a major meeting regarding the planning of the SKA (the headquarters are to be based here in the UK in Manchester), and the myriad different languages and nationalities represented was impressive to say the least. Over 24 major organisations from countries spanning 5 continents are involved in the project, ranging from universities to industrial engineering companies. New technologies, both software and hardware, are still being developed as a result of this project. Based on the huge data storage and transfer requirements of a machine as complex as the SKA, many of those new technologies are likely to feed straight back into society by offering profound improvements to computing resources like the internet. In fact, as the world’s largest project for sorting and storing data, the SKA is expected to be literally bigger than Google!

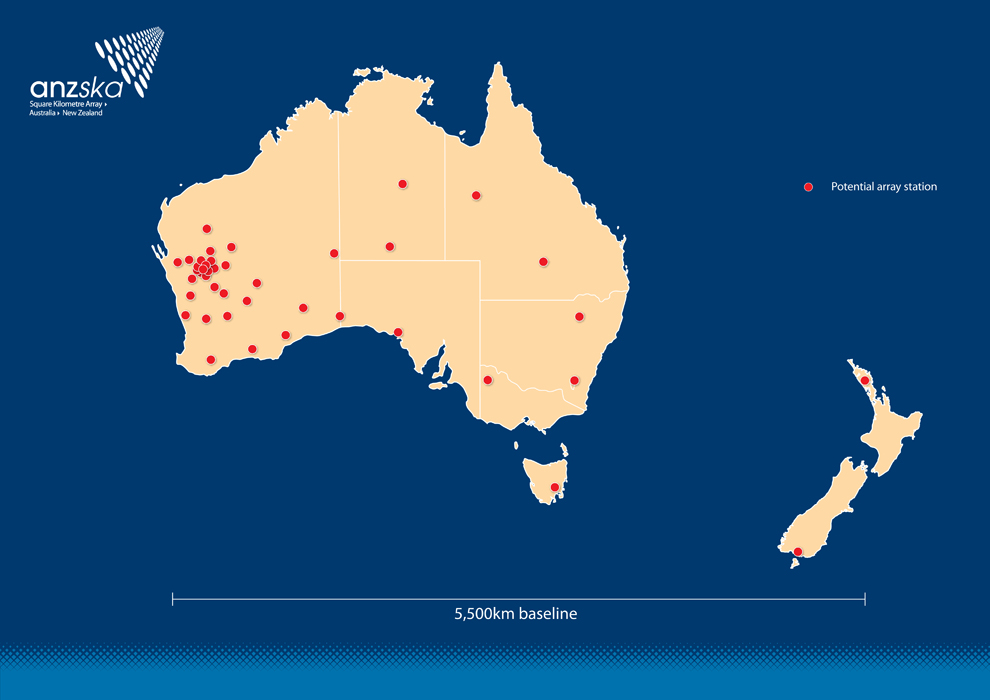

The most difficult decision, understandably, has been where precisely to build it. Humanity has an unfortunate tendancy to fill the atmosphere of our planet with noise, bouncing radio waves to and fro and filling the air with radio frequency chatter. A radio telescope array this sensitive needs to be placed somewhere quiet to gain the full benefits, and the most recent decision has been to effectively split the SKA into two components, to be built in Southern Africa and Australia. While this may seem like an odd thing to do, it actually makes perfect sense. The SKA actually has three types of antenna operating at different frequencies. Intended to cover a huge range of radio frequencies (from 70 to 100000 MHz), three types of antenna are needed, because no single technology can actually operate across such a wide range. So the decision was made to build the lowest frequency detectors across Australia, centred at Murchison in outback Western Australia. Murchison is blessed with being one of the few places on our planet which isn’t flooded with FM radio at the low end of the frequency scale. From a radio astronomer’s point of view, it’s the quietest place on Earth.

This is set to be complemented by the higher frequency steerable dishes which are set to be constructed across Africa. Both South Africa and Australia have put extensive efforts into developing the SKA, and Australian-developed technology is still set to be implemented in the African telescopes. This will mean a huge influx to the African astronomical community and numerous African nations won’t lose out on the economic boost from contributing to such a prestigious project. It’s an ideal situation where everyone wins.

All in all, it’s an exciting time to be an astronomer. An epic project like this is likely to attract all manner of researchers from across the world to both continents. Just maybe, it could also finally help us to answer the really big questions, like how the galaxy formed, how the Universe began, and whether or not there’s anyone else out there.

Follow

Follow

2 thoughts on “Radio quiet, please!”

Comments are closed.